The uncertainties that SMEs face when entering a foreign market

01/02/2023 - 5 min. de lecture

Le Cercle K2 n'entend donner ni approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les publications (écrites et vidéos) qui restent propres à leur auteur.

Jun Zhou is Entrepreneur, Lecturer & Consultant in Chinese Social Media.

---

European Commission has defined SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) in Commission Recommendation(2003/361/EC) as enterprises that employ less than 250 people and have less than 50 million euros and/or a balance sheet total of fewer than 43 million euros. With the latest data, there are approximately 23.1 million SMEs in European Union. (Statista, 2022) SMEs nowadays represent 99% of the business (European Commission, n.d.; European Commission, 2022) and contribute around 3.9 trillion euros to the economy.

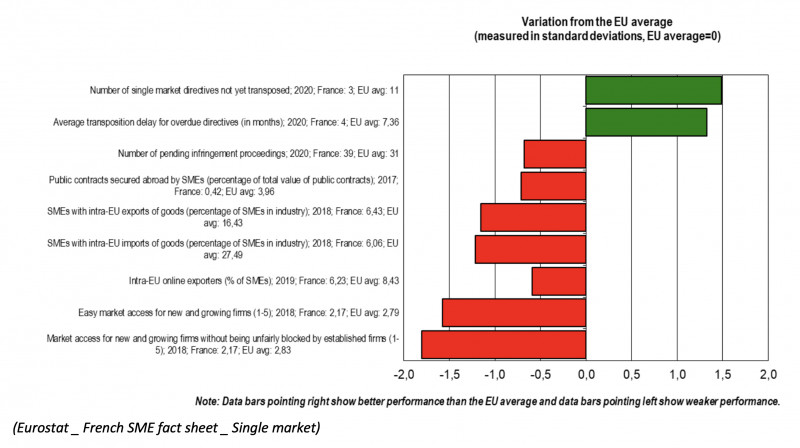

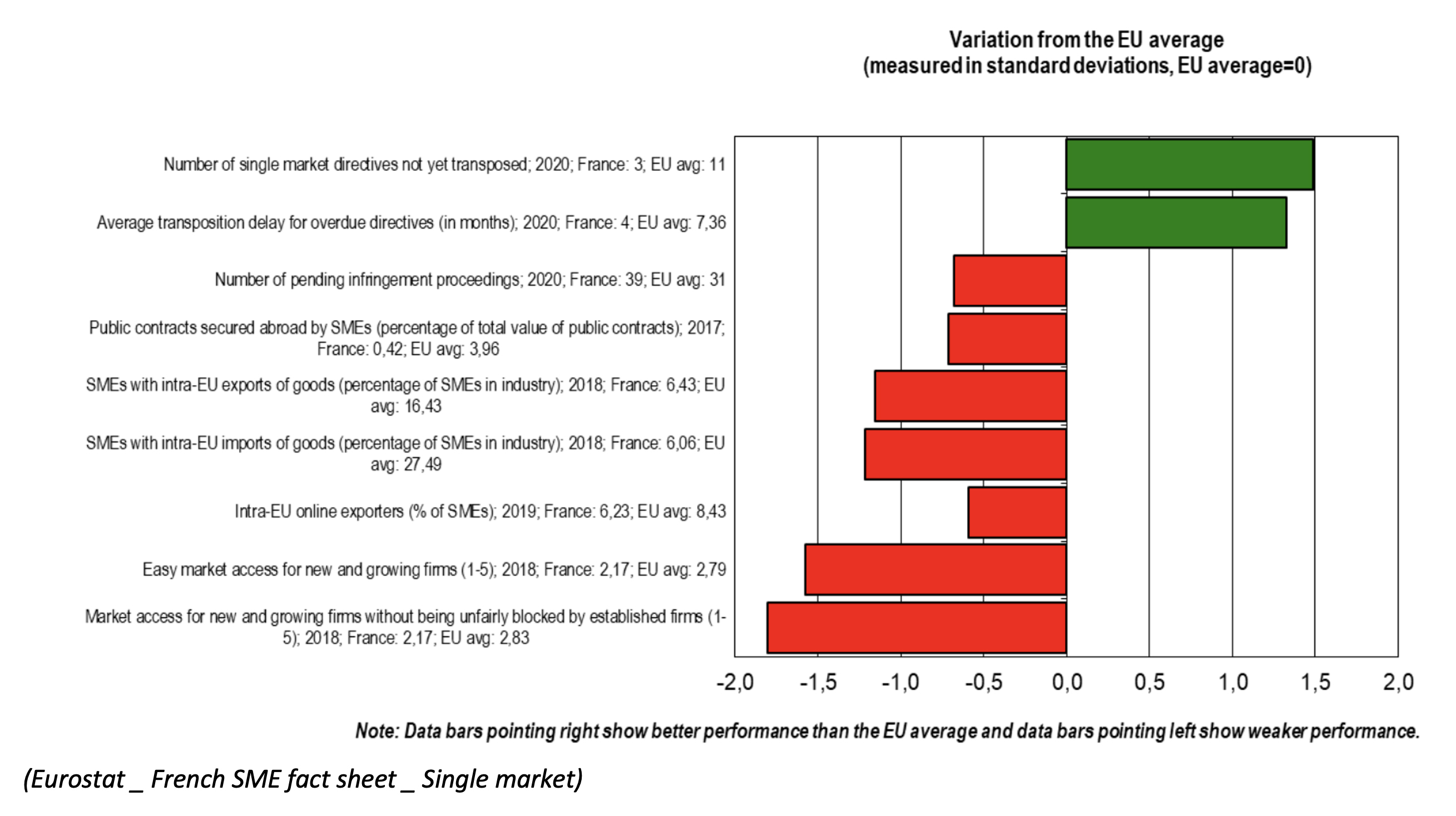

In France, in 2022, there are around 2.96 million SMEs, and they account for 99.8% of the enterprises. French SMEs have generated 51 % of the employment and have employed around 8 million people. With 42 % of value-added, French SMEs have contributed around 447 billion euros to the economy. The most recent data illustrates that France is ranked second in the number of SMEs and ranked third in value added of the non-financial business economy in the European Union. (Statista, 2022) Stronger participation by SMEs in global markets creates opportunities to scale up, accelerate innovation, facilitate spill-overs of technology and managerial know-how, broaden and deepen the skillset, and enhance productivity. (OECD, 2018) However, French SMEs are less involved in international trade and global value chains than the OECD average. (OECD, 2021) In 2018, only 6.4 % of French SMEs exported goods to the EU and 7% exported outside of the EU whereas on average 16.4% of EU SMEs exported to the EU and 11% exported outside of the EU. Less involvement in export from French SMEs hampers their potential to scale up, promote innovation, expand the market, and have economic growth.

A fundamental issue for foreign market entry is uncertainty. This holds true for any type of company, and it remains a relevant topic despite any period of time as the market consistently changes. Compared to the domestic market, the global market especially involves additional uncertainty. (Mascarenhas, 1982) Consequently, any strategic move to enter a foreign market requires SMEs to acknowledge and understand the uncertainties that they will face. It is also critical to identify the differences between uncertainty and risk in order not to underestimate the impact of uncertainty. The definition of uncertainty and risk is about two factors: outcomes and probability distributions. For risk, the outcomes are unknown but probability distributions are known, such as rolling a dice or flipping a coin. In business, risk concerns a situation with a known percentage of occurrences based on historical events. However, for uncertainty, both the outcomes and probability distributions are unknown, and so are the occurrences and impacts. In that, it is essential to classify the uncertainties, knowing that some uncertainties can be affected by the SMEs’ actions but some can’t. Exogenous uncertainty is defined as the situation when the decisions have no effect on the probability distribution or the observed outcome of future chance events. It is a type of uncertainty that is outside of a company’s control. Endogenous uncertainty regards the situation that the decisions can affect the uncertainty, and the uncertainty can be internal or external.

The primary uncertainty SMEs face is demand uncertainty (McGrath, 1997), and it is exogenous uncertainty. (Brouthers, et al., 2008) Demand uncertainty is about lack of clarity on the market demand and this will have a direct impact on SMEs to decide if they want to invest the production for a foreign market. Under high demand uncertainty, SMEs would try to lower the commitment of the entry modes and outsourcing of production is preferred. Moreover, demand uncertainty plays a substantial role for SMEs to choose their export channels. (Ipsmiller, et al., 2021) For example, when the demand uncertainty is high, SMEs tend to choose simple option channel that they will serve the foreign market from their home country and send salespeople to visit foreign markets regularly without having subsidies or co-managing with local partners. Acquisition is considered a popular way to enter a new foreign market, however, it is advised to use acquisition when the demand uncertainty is low. (Brouthers & Dikova, 2010)

Another uncertainty SMEs face is informational uncertainty. Informational uncertainty arises from a lack of reliable data and information or incorrect or misleading information about foreign markets. Informational uncertainty can be cultural and R&D related. This type of uncertainty can be resolved endogenously through learning, cultural training, and experimenting. (Cuypers & Martin, 2010) However, in the early stage when firms search and discover more information about unforeseen issues and barriers, they will re-evaluate their commitments going to the foreign market. It is warned that the role of information might also increase the perceived uncertainty in a subjective sense. (Nyström, 1974) Thus, for SMEs, rationalizing the informational uncertainty is essential.

Despite the entry mode SMEs would choose, network uncertainty is a critical barrier that cannot be overseen. It is the uncertainty regarding the relationships with customers, suppliers, investors, and partners in the host country. Developing and managing new relationships in a new market, and meanwhile balancing the existing network in the home country is a challenging task. It requires SMEs to build a thorough strategy and have a clear target for each phase. It is also essential to map out the differences, links, and similarities between the network in the host country and the home country. Network uncertainty can be endogenously decreased through SMEs’ actions. Accordingly, learning by experience is a key to tackle issues stemming from network uncertainty.

The political environment in the host country is also an inevitable factor to take into account during internationalization. Especially, for SMEs, with fewer resources to allocate than big groups, political uncertainty imposes big challenges when it comes to cross-border markets. Political uncertainty, posed as exogenous uncertainty, usually comes from two aspects: political hazards and regime change. Both can cause a huge impact on policymaking in terms of foreign trade, foreign investment, etc. Hence, import & export regulations, taxes, costs, asset values, and revenues can all be affected.

The challenges lie in front of SMEs - how to develop a tailor-made strategy for SMEs to scale in the foreign market.

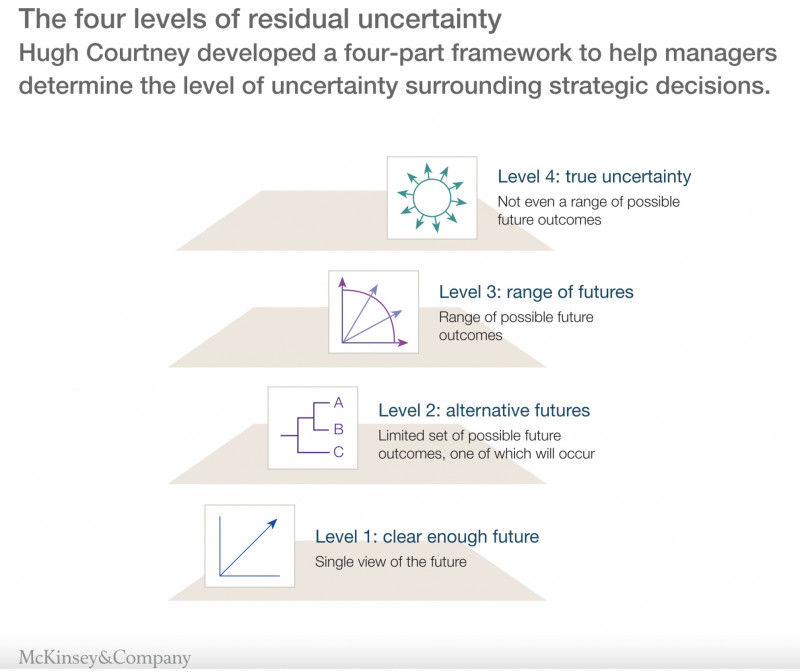

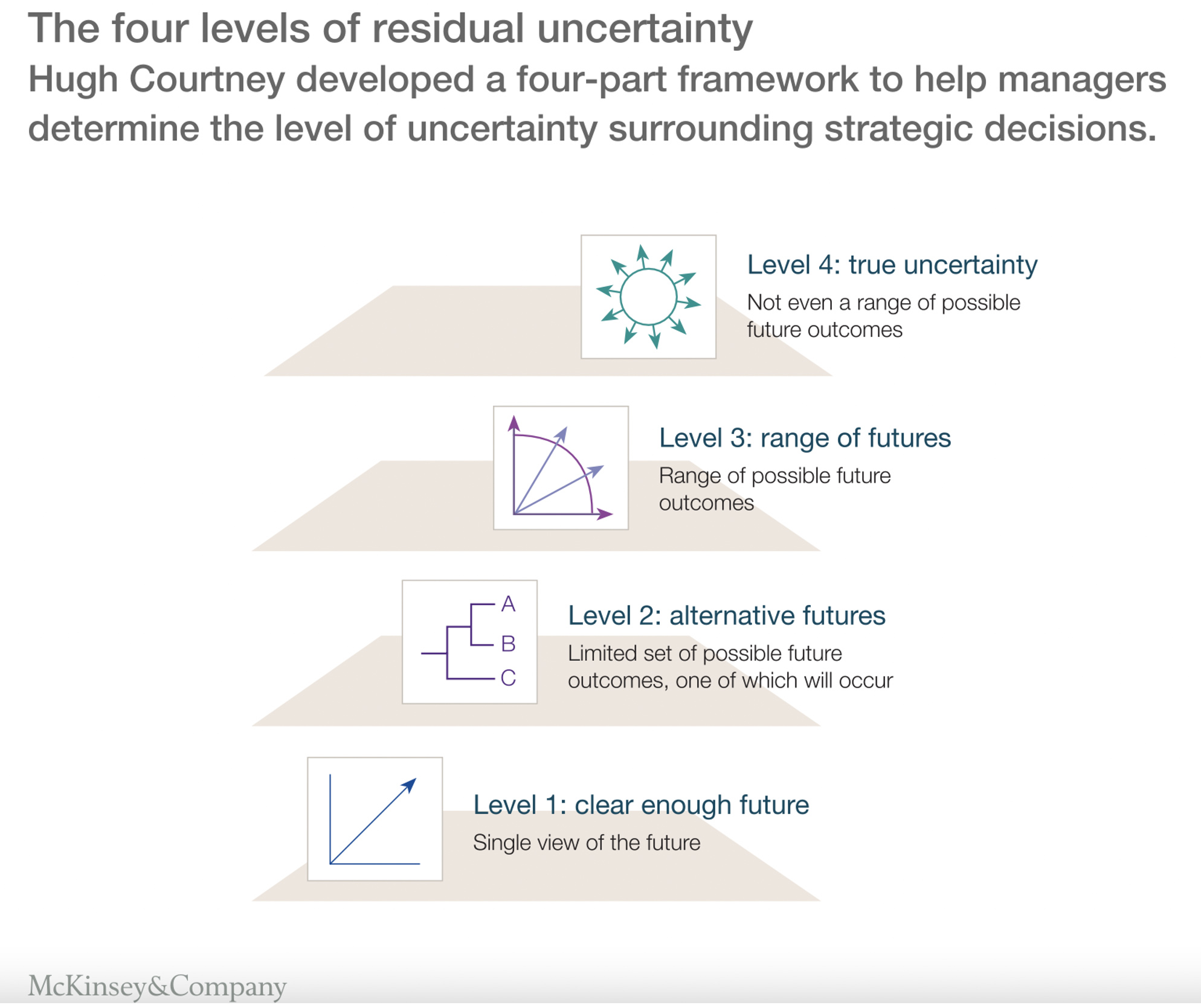

Four-level framework

An article published in McKinsey Quarterly in 2000, “Strategy under uncertainty”, talked about a four-level framework to determine the level of uncertainty in order to tailor the strategy. (Hugh G. Courtney, 2000) The level is set by the different types of future outcomes. Through this lens, SMEs can identify on which level they are facing the uncertainties, then choose and design the strategy accordingly, and finally manage the strategy via experiment and adaptation.

Global niche strategy

Since the early 1990s, researchers have been studying the internationalization of small firms, one of the key concepts been brought up several times is the global niche strategy. According to the paper "Coping with uncertainty in the internationalization strategy - An exploratory study on entrepreneurial firms" (Magnani & Zucchella, 2019), global niche strategy is executed through a series of strategic actions, including market creation, concentration on global clients, and control of technology and manufacturing capabilities. The findings entail that global niche strategy is not a reactive posture but a proactive identification of the needs and problems of customers. It is worth mentioning that many small firms that successfully scale up in foreign markets do not move from niche to mass market. As they mature, they tend to develop a portfolio of niche businesses in their existing technology platform.

As the internationalization process is rather long and difficult with full of uncertainties, it is critical to ask the following questions in order to be clear regarding whether and when to scale up internationally. Is the business already in a niche market locally? Is it worth joining the speed contest with global competitors? Is it short-term leverage or long-term potential than the home market? Given the complicity of the process for SMEs to scale up in foreign markets, hardly there’s a unanimous strategy to solve the issues arising from uncertainties during the scaling up. Nevertheless, dealing with uncertainty requires SMEs to acknowledge the uncertainty, have a plan, and use teamwork. Ultimately it is about designing a series of strategies covering diversified goals and priorities in both short-term and long-term.

---

Bibliography

- Statista, 2022. SMEs in Europe, s.l.: Statista.

- European Commission, n.d. Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. [Online]

Available at: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/smes_en - European Commission, 2022. SMEs Performance (France), s.l.: European Commission.

- OECD, 2018. Fostering greater SME participation in a globally integrated economy, Mexico City: OECD Publishing.

- OECD, 2021. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Mascarenhas, B., 1982. Coping with Uncertainty in International Business. Journal of International Business Studies, 13(2), pp. 87-98.

- McGrath, R. G., 1997. A Real Options Logic for Initiating Technology Positioning Investments. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), pp. 974-996.

- Brouthers, K. D., Brouthers, L. E. & Werner, S., 2008. Real Options, International Entry Mode Choice and Performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45(5), pp. 936-960.

- Ipsmiller, E., Brouthers, K. D. & Dikova, D., 2021. Which export channels provide real options to SMEs?. 56(6).

- Brouthers, K. D. & Dikova, D., 2010. Acquisitions and Real Options: The Greenfield Alternative. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), pp. 1048-1071.

- Cuypers, I. & Martin, X., 2010. What makes and what does not make a real option? A study of international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, Volume 41, pp. 47-69.

- Nyström, H., 1974. Uncertainty, Information and Organizational Decision-Making: A Cognitive Approach. The Swedish Journal of Economics, 76(1), pp. 131-139.

- Hugh G. Courtney, J. K. S. P. V., 2000. Strategy under uncertainty. [Online]

Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/strategy-under-uncertainty

[Accessed Dec 2022]. - Magnani, G. & Zucchella, A., 2019. Coping with uncertainty in the internationalisation strategy. International Marketing Review, 36(1), pp. 131-163.

01/02/2023